If you went into his room during the once-in-a-lifetime chance he was out of it, you could smell the more than faint odor of decay. The “old man” smell, as it were…with hints of urine and rotten eggs thrown in, to boot. It was the foul stench that none of them could avoid after a certain age. Especially if they weren’t rich enough to semi-mask it with an expensive scent, or generally take better care of themselves in such a way that would “suspend” the decay that leads to that unmistakable odor. In any case, when the lodger first moved in, no one could have anticipated what the reality of his presence would actually entail. On the one hand, Enid, Roger and their thirteen-year-old daughter, Billie, couldn’t have asked for a better “tenant.” Zach was practically invisible, scarcely emerging from his room except when one least expected (therefore, least wanted) it. On the other, the knowledge of his constant presence in the apartment was ominous—as though he could pop out like a jack-in-the-box at any blood-curdling instant.

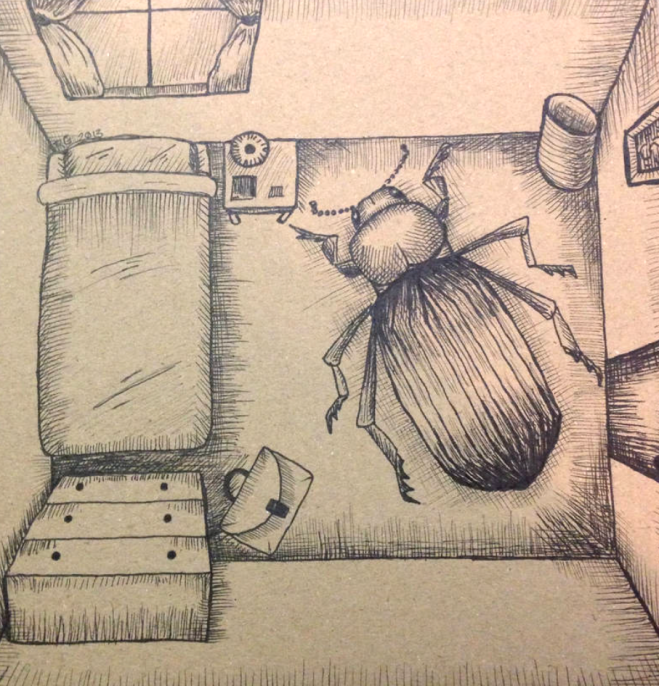

To the Krantzes, especially Billie, this was no way to live. No matter the six hundred dollars he monthly contributed to the rent. A contribution that would get Enid and Roger that much closer to paying off their mortgage, owning their apartment and swiftly telling Zach to get the fuck out. Unfortunately, it was going to be at least a year before that could be even a remote possibility. In the interim, the Krantzes would simply have to put up with the “unintrusive” yet somehow sinister presence of Zach in their home. It was that tincture, in fact, that made him so Gregor Samsa-esque. Zach’s ability to stay in his room most of the time (nay, all of the time) was a result of his recent status as a retiree. Indeed, both Enid and Roger found it odd that someone in his age bracket would be desperate enough to rent a room. Particularly as he seemed to have a sizable pension. But maybe, Enid and Roger reasoned, he was simply trying to be “smart” about money. To “make it last,” as it is said. That’s what the couple told themselves to make it “okay.” To ease their minds of the notion that he was a creepy loser who might have serial killer predilections that could very well take aim at Billie. And, of course, there was the natural American fear about any older man being around a teen girl.

But, as usual, the promise of a steady flow of “easy” money trumped all other logic and reason—eradicated all sightings of the color red amid the flags surrounding Zach. Whose name, by the way, seemed fake, not at all believable for someone his age. Did the name Zach even exist in the fifties? Enid had to wonder to herself. But she didn’t bring it up to Roger. She had already said enough in protest about the matter, and it was clear that no argument or concern was going to change Roger’s dollar-tabulating mind about this. And since Enid wasn’t the higher earner between the two of them, what say did she really have in the matter? Her input, as usual, was a matter of “ceremony.” A gesture signifying nothing.

So Zach moved in, seeming, at first, to be “pleasant,” bearable. An acceptable enough addition to the household. Best of all, he needed no cabinet space in the kitchen or bathroom, which, although as unsettling as Zach himself, was especial music to Billie’s ears. Mainly because she had an arsenal of beauty products in the bathroom that she absolutely didn’t want to be bothered with adjusting or maneuvering to accommodate some unkempt old man. And when Billie thought about it more measuredly, it made sense that Zach would have no need of any bathroom cabinetry. He had clearly given up on life, if his appearance was an indication. Tattered clothes, scraggly hair and beard and a perennial stink (the one that veered on the side of rank patchouli as much as it did decay) that lingered in the kitchen and bathroom—the only areas he dared enter—whenever he passed through.

To Billie in particular, everything about him screamed, “Pathetic!” He obviously wasn’t one of those old men from which any wisdom could be gleaned. If anything, he served as an exemplar of what not to do in life. What’s more, Billie had the sneaking, terrifying suspicion that Zach had moved into the room specifically to die, and she dreaded coming home one day to the unignorable stench of a corpse (as opposed to Zach’s usual unignorable stench). This was a phobia she chose to keep to herself, not wanting to burden her parents with her worries when they seemed so much less stressed about their finances. Even if they did appear to be just as ill-at-ease with Zach in the abode as Billie. But, unlike Billie, they didn’t do everything in their power to avoid any potential encounter with Zach in the common areas. In fact, Billie would meticulously time her entire schedule around not running into Zach.

For the most part, it worked out…except when he seemed steadfastly determined to cross paths with her. For there were times he would dilly-dally in the kitchen, almost as if to spite her. To force her to come out sooner or later so that she would have to face him. Because her addiction to the bathroom, with its mirror and her toiletries, required that she always pass the kitchen in order to access it, thereby automatically incurring the risk of being seen by Zach and, consequently, subjected to a dreaded round of painful small talk. Dreadful and painful not just because his life was so boring (practically vegetative), but because every time he opened his mouth, he revealed just what a narrow-minded misogynist he was. Even when he was attempting to “relate to” her as a “Gen Zer.”

As was the case with most adults, this meant bringing up Billie Eilish. Someone that Billie, despite her name, actually had no interest in. Nonetheless, she tried to oblige him in a conversation about the neo-pop star because he was so clearly grasping at straws. But when he proceeded to carry on about how all of Eilish’s success was the lone result of her brother’s “genius,” that’s when Billie fully fathomed that he was one of those: an old guard man who could never give a woman the credit she deserved. And then there was the time Zach casually mentioned that all the colonizers were doing was “civilizing” indigenous people who otherwise wouldn’t have been “outfitted” with the benefit of universities and, eventually, malls.

Knowing it was useless to try to make a man like that see reason/reality, Billie just bit her tongue until it almost bled—nodding along until it was mercifully over. Which, to her, felt like hours later (in truth, these rare “tête-à-têtes” lasted all of about five minutes). And that’s when she could reappreciate Zach’s usually consistent tendency to remain in his room. His Gregor Samsa existence—being contained within the same four walls because of his grotesquerie and inability to contribute to society (apart from his middling rent fee)—was no longer creepy or ominous to her, but a welcome reprieve from the torment of being subjected to his on-the-verge-of-death stench and conversation skills/topics of choice that were about as enjoyable as the sound of sandpaper repeatedly rubbing against wood. Come to think of it, Billie would have preferred that any day of the week to listening to Zach run his mouth. Alas, pieces of sandpaper aren’t compensated for the work they do and thus cannot pay rent. Though that would certainly be some societal metamorphosis all its own.

In the meantime, the Krantzes would have no choice but to endure the human sandpaper that was Zach. In due course, the mortgage would be paid, and they could ask him to leave. That is, if he didn’t die in the room first. Though it might take several days to note the distinction between his natural smell and the smell of death.