There is an unaccounted circle of hell that Dante never mentioned in print. I won’t number it, but it’s there, and I’ve endured it. It involves the unique hell of being forced, as your adult self, to watch your parents raise you in exactly the same way that they did before. To repeat the same mistakes that you weren’t so hyper-aware of the first time around, but can now see (quite literally) with crystal clarity.

Worse still, the only one who can see you watching is your younger self. Your parents have no idea. So that when you’re screaming and crying for them to stop doing that, to stop making the same mistake that’s going to render you, ultimately, as such a fucked-up, emotionally wounded human being, they will have no awareness of your presence. Only your younger self can see that you’re distraught. And being that she is still too innocent and naive to know any better, she will look up at you and tell you that it’s okay, Mom and Dad are “trying.” “Doing their best.” Shit, if that was their “best,” I’d hate to see what their worst was.

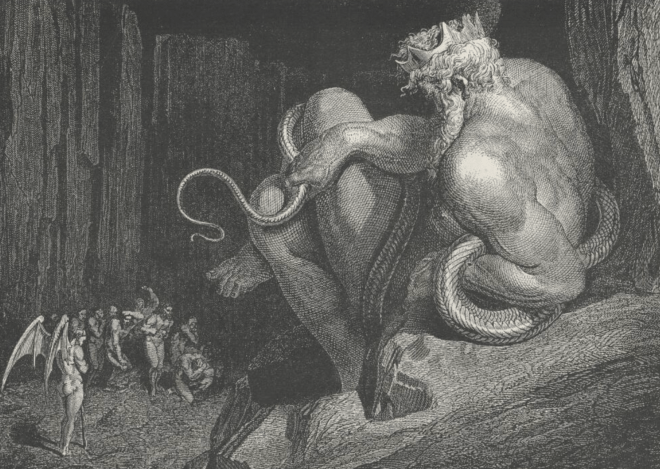

I don’t know how I came to be in this particular, previously untapped circle of hell. Before this, I was peacefully relegated to the second circle: lust. Like most people who lived in New York at one time, I had fallen prey to some decidedly Theresa Dunn-in-Looking For Mr. Goodbar antics. Lust was not only inevitable, but encouraged. The name of the proverbial game. What else was there to do in New York, as a broke person, besides have one-night stands? I never made enough money to find out, relying on the kindness of drink-buying strangers to get me through. Except it wasn’t really a “kindness,” was it? There was always an unspoken “payment” to be given by the end of the night. And I happily gave it. I knew what my “role” was in the permutation, willingly invited it. “Asked for it,” as men like to say. And I was fine with the “endgame” result: the second circle of hell.

Yes, I felt quite comfortable among my lusty brethren, including Cleopatra, Madame du Barry and Mae West. I would have had no trouble at all languishing for the rest of eternity in that circle. But no, one day I woke up and found myself in this previously unidentified one. I don’t quite want to call it the tenth circle, because, for all I know, there are others that haven’t yet been unearthed. I can only hope that’s the case, as it means I won’t end up being stuck here forever, forced to watch my parents, and my father in particular, fuck me up in real time.

Watching it all unfold like this, I’ve also been forced to remember some things I apparently managed to block out. Like how my father used to give me shots of grappa to keep me quiet and go to sleep in the two- to three-year-old age range. I wonder what kind of developmental growth that stunted later on. What if my entire brain chemistry could be different were it not for my father’s fast and easy “go to sleep” method? I’ll never know now. Meanwhile, where was my mother to defend me from such methods? She was more absentee than a fifties-era father. That’s what I see. When she does bother to show up, she’s often beleaguered and uninterested in engaging with me at all, let alone holding me. Allowing me to “attach” in any meaningful or memorable way. It’s no wonder I had such a difficult (read: nonexistent) relationship with her later on, notably in my teen years.

And yes, I was subjected to watching those unravel again from my adult perspective as well. I thought this unnamed circle of hell would at least spare me that, but no. Why would it? After all, the teen years are the most horrific. Especially as they strike the balance between no longer being “raisable” and the immediate aftermath of how you were raised as a child. In my adolescence, I feel I was surlier than most girls. More prone to rage and mood swings that couldn’t be explained—beyond, of course, the usual go-to of: “It’s just hormones.”

But it wasn’t. It was my parents. The way they had shaped me to suppress all my emotions and be a “good little duckie.” Or, grosser still, a “good little girl.” That conditioning had turned me into a ticking time bomb. One that went off in fits and starts in my teen years (you know, with mild shit like shoplifting and pyromania) and then completely exploded in my twenties, when I started Looking For Mr. Goodbar.

Funnily enough, practically the second I moved away from my hometown, my parents were quick to forget about me altogether. I couldn’t help but notice, after all, that the phone only seemed to work one way, with my mother and father also being the ones to typically end the conversation first with an, “Okay Janie, we’ve gotta get going now. Nice talking to you.” But I knew they didn’t actually think it was “nice” to talk to me at all. That it was instead a burden, an albatross. An eternal duty they hadn’t fully understood the weight of signing on for when they conceded to having a child. I can only be thankful that they stopped at just having me, and not subjecting some other poor soul to their combination of negligent and brutal parenting.

Oh look, now I get to watch me sobbing in the corner of the living room after a so-called friend at my birthday party stole my favorite toy right after I had unwrapped it and my mother took that bitch’s side instead of mine. Telling me that I ought to learn how to share. Or maybe my “friend” should have learned not to be such a cunt at someone else’s birthday party. But no, my parents never saw things that way. In short, they were never on my side. And it was this barrage of “tiny” incidents that amounted to one massive thesis statement on how they truly felt about me. Which was to say, not that fondly at all. They were not “protectors” but “throw you to the wolves’ers.”

Honestly, I had no idea what I did in my life that was so horrible as to deserve this circle of hell until I reached the phase of my “raising” where I ended up killing both of them on a visit home from New York for Christmas one year. Ah yes, I suppose I had blocked out that minor indiscretion as well. The things we must blot out in order to go on living, eh? Or even to go on dying.