When her ex broke up with her, she knew that, in the end, the joke would be on him. That not only would he be sorry in the long run, but also deeply embarrassed for having had the audacity to think that Nora Levinson would never amount to anything. Maybe, in this regard, she shared a certain similar plight to Nora Helmer in A Doll’s House. Torvald, too, doubted his wife. Doubted her capabilities apart from being mere “plaything” for her husband, and even for “outside men” like Krogstad and Dr. Rank.

Well, both Noras would prove their underestimating significant others wrong. Nora Levinson far more than Nora Helmer, who had such limited options—what with being a woman in the nineteenth century. Clearly, there was a reason why Ibsen chose to end the play simply with Nora leaving, not bothering to show a more concrete fate for this “rebellious woman,” which likely would have involved resorting to prostitution. If anyone wanted to be honest with themselves. But theatergoers only have so much capacity for “honesty.”

Luckily, Nora L. lived her life outside the constricting parameters of theater (and the nineteenth century, for that matter), and would be able to more tangibly (and bombastically) live out her revenge fantasies for success against her own version of Torvald. Whose name was, rhymingly enough, Griswald…but he went by Grizz. What kind of man who willingly called himself Grizz had the right to pass judgment on Nora? To make her feel as though, somehow, she was not “good enough.” And what would be good enough to a person like that, anyway? She imagined if she offered to be his sugar mama, that would suddenly make her worthy. So long as you kept a man on your tit in more ways than one, he was bound to be left with no choice but to stick around.

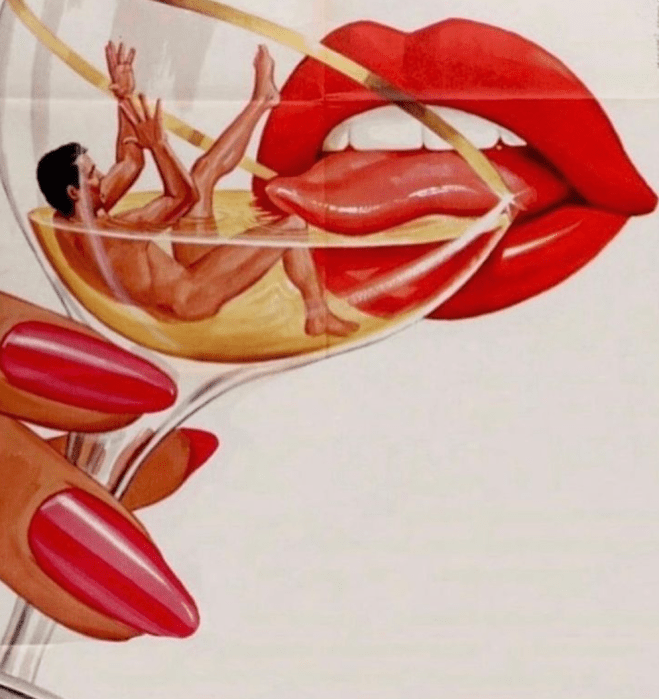

And from this sprung the idea of how she would seek out the ultimate revenge. Make as much money as possible, secure a new, younger “man” (they were all boys, of course) and become his sugar mama in a very public way. Parading their lavish trips together and all the things she bought him on her socials and stories, the ones that Grizz, without fail, continued to look at.

That’s what all ex-boyfriends seemed to do. Creeping in and out of the digital “slices of life” their former girlfriends made available to them, as though to—what?—confirm that they had made the right decision by abandoning them. Who can say? All Nora knew was that she needed to use this fatal flaw present in most ex-boyfriends to her advantage, forcing him to realize that, yes, he did make a very grave mistake indeed in choosing to “cut her loose.” In choosing to assume that she would never “become something.”

Well, hell hath no fury like a woman told that she’s worthless. Nora knew all along that wasn’t true. If for no other reason than her body. For what was a woman’s body if not “commodifiable,” an endless wellspring of potential income, when sexualized? So Nora did the thing she knew she could have always done—it was just a matter of time: sell herself. It began, as all things do, casually. She would charge select users of her online account various fees for various “services.” Though all of these services involved remaining largely stationary. She received such a big income for so little physical exertion on her part, now that most sexual acts had been relegated to the immaterial world. Except that she was starting to find that the bigger bucks would arise out of in-person “encounters.” So Nora branched out, homing in on the “serious men” who could pay her a greater amount for the time and trouble of offering her flesh more corporeally. And, of course, she would always go to them—never allowing these johns into her own inner sanctum (just the inner recesses of her rectum).

After enough months spent building this following of well-paying “regulars,” Nora had squirreled away (wasn’t it Torvald who had called Nora H. a “little squirrel”?) an ample sum. One that could set her plan for revenge upon her ex in motion. So she placed her sights on someone ten years her junior: Rhett Wilton. The two had orbited one another for a while, thanks to Nora’s predilection for befriending slightly younger women that, for whatever reason, saw her as some kind of “inspiration” (particularly after she joined the skin trade). Though she certainly had no idea why, she didn’t question it. Instead, she used it to her advantage to meet boys in Rhett’s demographic. The ones who were more deserving of a sugar mama than so-called men of Grizz’s age, who should have already learned how to be self-sufficient and to live with the cold, hard reality of that.

The joke, she thought, was most definitely going to be on Grizz once he started to see all her decadent posts with Rhett. But, ultimately, it was on her. He had stopped looking after almost a year of continuing to “peep in.” At present, he didn’t care. He had moved on to some other girl that he could actually take care of. And that’s when Nora understood what had been the real cause of their breakup: she was actually too independent, too “a woman with a mind of her own” for Grizz’s taste. All along, what he really wanted was someone more malleable. Someone who wouldn’t call him out on his bullshit or question whatsoever anything he said or did. Just as it was with Nora H. and Torvald.

What’s more, her own “third act finale”—prostitution—was exactly what would have happened to Nora…had Ibsen been bold (or “cynical”) enough to reveal the fate of women who dared to leave their husbands in the nineteenth century. Luckily for Nora L., views on sex work have come a long way since the 1800s. Though not so far that it made it any easier for Nora to find a more age-appropriate boyfriend once Rhett abandoned her for a dalliance with a much more flush sugar daddy. Another difference between now and the nineteenth century: male sexual fluidity had become a much greater hindrance to romance for women.