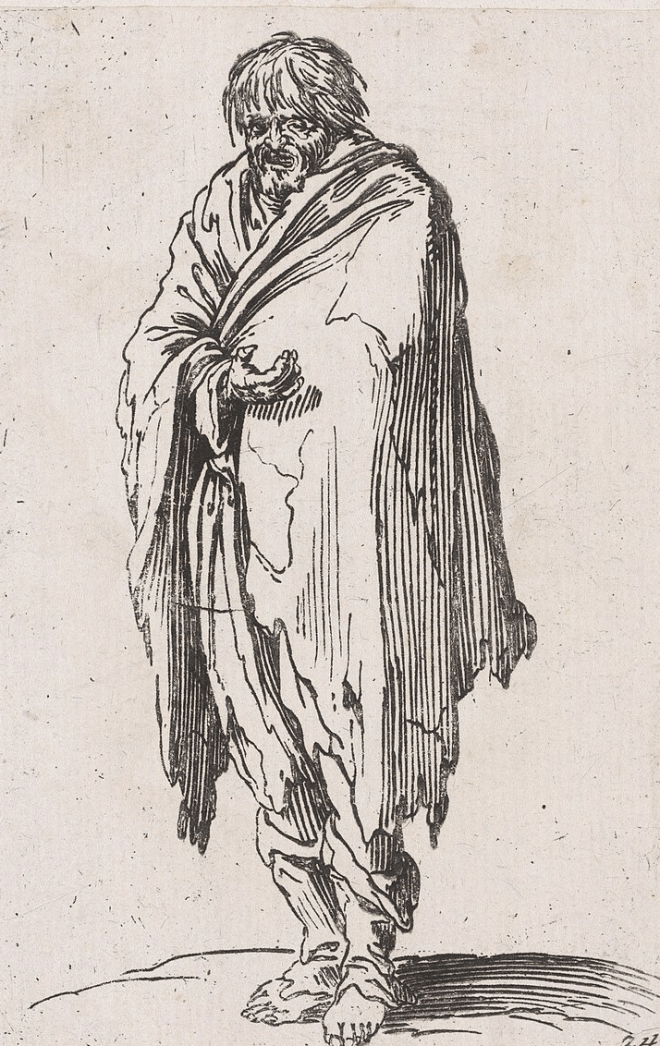

Do not say that the beggar does not work for his money. I happen to know for a fact that he does because I saw him early one morning when I had to be out on the street before seven a.m. As a man of leisure, that’s a true rarity in my case, but I had to catch the train to London from Gare du Nord, in pursuit of pleasure, not work. Which is part of why I felt the slightest pang of guilt when I saw him there, already hustling for a euro. Granted, he was only sitting there—it’s not like he was standing or bopping around and busking. Displaying some artistic talent that he had perhaps given up his whole life for (because they say that refusing to make money is the equivalent of giving up your life as opposed to taking it back). Even so, it takes a certain kind of skill to be up that early when you could just as soon be continuing to sleep on a still-quiet street. In those hours right before the city bursts to life. Besides, it wasn’t as though this man had any “place to be.”

But, in truth, he did. Knew the best times and places to hit up strangers for “spare” change. For this beggar showed ingenuity, the kind of “can-do” attitude that employers are always talking about, saying how much they desire this quality in an employee. And here this man was, displaying said attribute and so much more, yet he had obviously never been seen as viable enough by any employer. Otherwise, he wouldn’t be on the street right now (unless it was a conscious rebellion). Maybe the one “necessary” quality he had lacked all along was being a “team player.” Maybe this lone “defect” is what eventually led him to a life on the sidewalks of Paris. Where, in his way, he was thriving with his hard-working, but “too individualistic” style of moneymaking. At least this way, though, he didn’t have to pretend anymore to give a fuck about some company’s bullshit cause. And make no mistake, every company’s “cause” is bullshit, an elaborate smokescreen meant to faintly conceal the vanity of whoever is really running the show (a.k.a. the one controlling the purse strings).

Yes, this way, all the money was going into his own pocket in exchange for the dignity-eradicating efforts he made. Those forced to endure a “middleman,” so to speak, to get their money couldn’t say as much. Or so I reasoned as I approached the metro, clocking him in his rigid perch on the top step, shouting shamelessly, “Bonjour madames, messieurs, avez-vous quelques monnaies pour moi?” It sounded downright proper. Especially because he didn’t use a cruder word for coin, like pièce. As in: this world and its entire galling setup is a pièce de merde.

I stopped and watched him repeat this phrase like a parrot for about two minutes, counting three people who were willing to oblige his request. If things kept up at this rate, he would be well on his way to making an amount of money that was equivalent to minimum wage—maybe even more on a really good day. So again, I emphasize: do no say that the beggar does not work for his money. He does indeed—and he does it shrewdly. Far more shrewdly than the tax-paying simps of the world. What’s more, he does it only at the peak hours of the day, when he knows most foot traffic exists, therefore the highest potential for securing some alms. He is, hence, the very definition of “working smarter, not harder.” Because why should a person pretend to work all day when they’re not always yielding a maximum profit from it? Worse still, always wielding the same exact profit from it no matter how hard they work (which is what’s expected from an employer, lest their employee wants to get sacked). Where’s the “good sense” in that? Of course, anyone who ever said that capitalism had good sense was usually a Republican. Or a “centrist” Democrat (these days, a synonym for Republican).

The beggar, however, had technically “opted out” of capitalism altogether, and yet, simultaneously remained enmeshed in that system, regardless of how far away he had gotten from it—whether by choice or through a series of unfortunate events. While it’s more commonly the latter, some people (usually men) did choose to “exit society” willingly. And, in their way, the men who retreated permanently into the basement of their parents’ house weren’t that unlike the proverbial beggar on the sidewalk. The only difference was that they had been blessed with the good fortune of “having a place to land” when they could no longer endure the rigors and demands of “society.” Oh fucking society, that ruiner of all wills.

The beggar I was looking at (perhaps even starting to stare a little too creepily at) would be perfectly “respectable” if he had ended up living at his parents’ house, maybe somewhere in the French countryside if the birth lottery had worked out in a more favorable way for him (because, in truth, no one really wants to be born an American anymore, let alone living in one of its illustrious basements). But because this beggar didn’t have that luxury, he was a pariah, a “dreg” cast out by the “functioning members” of this fucked-up, no-win structure for “living” (which often entailed doing the exact opposite—engaging instead in a slow, agonizing death). Because a win for a few is pretty much a loss for all.

Even so, studying this beggar from afar (like he was the answer to the riddle of the sphinx or something) gave me pause to wonder if maybe he was the real winner, after all. “Gaming” the system by no longer being a part of it, yet still extracting money from people who foolishly (and oh so willingly) were. Of course, I wasn’t one of those people, but that was neither here nor there. Like him, I had “gamed” the system—and I think we both possessed an air of self-satisfaction about that. Even if I had gamed it in a much pleasanter, less debasing way: by inheriting my wealth.

So I threw a bone a.k.a. coin at a fellow brother in Dropping Out of Society on my way down to the metro…only to trip down the stairs and sprain my ankle in the process. That’s when I knew for sure: I would never again deign to “stay humble” by 1) taking the metro or 2) trying to save a few (like a hundred) euros by choosing an early train time. From here on out, it was chauffeured car rides and afternoon trains to London only. Thus, that was the day I fully comprehended the wisdom of the beggar and the rich man.