Elena stood in the parking lot outside the Casa Italiana smoking a cigarette. She didn’t realize how bitter her expression must have looked until one of the other volunteers, Maris, approached her and said, “Why the sour face?” If Maris wanted to know the truth, the reason for her so-called sour face was that she didn’t want to fucking be there. She had been roped into volunteering for this event as a result of her mother’s skills in the art of emotional blackmail. Yes, Renata Soltano had a master’s degree in How to Get Your Daughter to Do Things She Hates by way of her constant nagging, her relentless repetition—verbalized through squawking—of the thing she wanted you to do. And what she wanted Elena to do was contribute some of her food from the restaurant where she had only recently become the head chef.

That said, Elena wasn’t trying to rock the boat so early on with this freshly acquired clout. She wanted to ease into taking advantage of her new position. Except, in this case, there was no advantage to her, only to her mother’s reputation among the parishioners of St. Peter’s Italian Catholic Church. A church that Elena had shunned long ago, somewhere in her early teens, when she realized that being Italian American wasn’t all it was cracked up to be (try as Lady Gaga might to yammer on and on about it and how she was it—though if she really was, her put-on accent in House of Gucci wouldn’t be so affronting). Oh sure, it was great for the food, but when it came to dealing with the guilt, passed down from generation to generation like a curse, well, that was more than Elena could bear.

This was part of why she made a concerted effort to emancipate herself when she was sixteen. A decision that, Renata continued to argue to this day, was what caused her father, Vince (a.k.a. Vincenzo), to have a heart attack in his mid-forties. Renata never forgave Elena for the “gall” she displayed in doing something so “egregious.” But, when Elena actually went through with it and found herself living alone in her own Downtown apartment, she honestly couldn’t have cared less if she truly was the cause of her father’s premature demise. Living without the oppressive presence, the judgmental hovering of both her parents was too glorious and incredible for her to feel guilty about. And, as the years went on, she never regretted the decision she made. For if she had stayed under Renata’s thumb, there’s no way she ever would have “allowed” her to attend The Chef Apprentice School of the Arts (better known as CASA), let alone start working at a restaurant so she could pay for her education. And not just any restaurant either: Maccheroni Republic. To Elena, it was a good sign that the manager saw something in her that was worthy of working at an establishment that had asserted itself as one of the premier Italian spots not just in Downtown LA, but the entire city.

Over time, she started working her way up the chain in different Italian restaurants throughout Los Angeles, always ascending to the highest point just before chef. That’s when she would usually “cut the cord” and go elsewhere, ready to begin at the bottom again every time. Like she was afraid of success or something. However, at the restaurant where they had just made her head chef, Gaetano’s, Elena had been met with a complication in her usual plan to abandon ship before she ascended too high on the chain of command. That complication was this: she had fallen in love with one of the waiters, Carlo (that’s right, Carlo, not Carlos). Anyone who has even a cursory knowledge of the restaurant business, thus, ought to know that the only way she could ever see him somewhat regularly was to work in the same place that he did. This is what had caused her to “lose track of the time,” so to speak. To forget to quit before she could go any higher within the organization.

But, soon enough, Gaetano himself was insisting that Elena take the helm in the kitchen, and now here she was. Somehow only using this recently gained power to assist her mother. The one person in her life who was “unmoved” by her cooking, yet now she wanted to wield Elena’s talent for her own social gain. And, for whatever reason, Elena was only too willing to allow herself to be exploited (granted, being exploited is, in general, the “deal” when it comes to working in the restaurant industry). Both emotionally and physically. For it was no easy feat to transfer all the food she had prepared to Casa Italiana. Something she did mostly with Carlo’s help, not wanting to draw too much attention to the fact that she was using the restaurant’s resources for a charity gala. One intended to raise money for another nearby Italian restaurant that was fated to go out of business if they couldn’t gather enough funds to pay the rent the following month, when the price would go up.

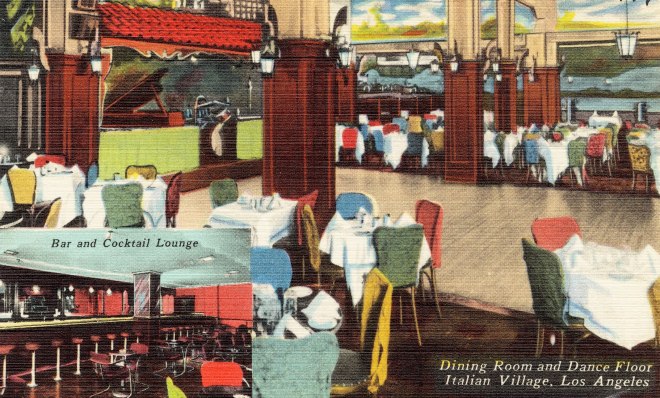

It was happening more and more at these “institution”-type places. For being an institution, apparently, didn’t mean much to people anymore. Especially to those who hadn’t been in Los Angeles long enough to understand that its cultural fabric was inherently tied to food. And not, as is so often touted, “just” Mexican food. As Elena would argue until her dying breath, L.A. was, outside of Italy itself, the best place in the world to find authentic Italian cuisine. Much better, in fact, than New York, where the mutation of Italians into Italian Americans bred an entirely different kind of cuisine. One that was not actually Italian, but some bastardized version of it. And not in a good way.

On the exterior of the Casa Italiana, it is written, “Ars Vita Religio.” In other words, “Art Life Religion.” One supposes those three things are the foundation of “being Italian”—though the words “family” and “food” were mistakenly left out. It was the latter that Elena found the most meaning in. Not just as a person of Italian descent, but as a human in general. To her, there was nothing that couldn’t be solved—or at least slightly mitigated—with the presentation of the right dish. That is, unless that something had to do with Renata. There was no amount of “bread breaking” that could unite them, compel them to find “common ground.” Years ago, this had made Elena somewhat depressed, but she learned to get over it. To take her relationship with her mother for what it was: bad. Over the decades, and with the help of her therapist, she came to understand that a key reason for her “obsession” with food was that it provided the level of comfort that her mother never could (this being somewhat antithetical to the stereotype of smothering Italian matriarchs).

But lately, she was starting to notice her former enthusiasm—her sense of perfectionism—when it came to food was waning in direct proportion to how much more invested she had become in her relationship with Carlo. Which was actually quite terrifying in that if she made any sort of culinary misstep as the head chef at Gaetano’s, she would lose her job, therefore her access to Carlo. The “thing” she was starting to care about more than food. This was a first for her, and an unwanted one. She had always assumed that the sole benefit of growing up in an emotionally stunted household was that it meant she would never have to worry about attracting someone who would want to be in a long-term relationship with her, thereby giving her all the time she needed to focus on perennially fine-tuning her culinary skills.

However, to her utter shock, Carlo was unfazed by her neuroses. For he, too, had grown up with two Italian parents constantly at each other’s throats. Some people called that nothing more than “the Mediterranean way.” Elena called it trauma inducement. Carlo understood that, grasped completely where she was coming from. She didn’t need to explain things to him—about family or food—that she had to when she dated other men. Men who weren’t Italian, or at least Italian American. Men who didn’t even know that so much of Los Angeles’ history was rooted in the businesses, movements and arts that Italians brought to it. They had come to the city even before the diaspora in New York. Come to the city before California itself was quite literally put on the map by the Gold Rush. Yet, somehow, their “group” seemed to remain invisible. Underlooked. That, Elena suddenly realized, was why she was really doing this. Contributing her time and her food to this gala. It wasn’t for Renata, or to “please” her in some way. It was to keep holding on to the ever-waning Italian roots that Los Angeles (or rather, its latest influx of residents) persisted in trying to sever. To write off by treating its remaining vestiges so carelessly. And that started, first and foremost, with its eateries.

Stubbing out her cigarette after taking a final drag, Elena knew what she needed to do if she wanted to succeed in her mission to preserve, in any small way she could, this increasingly cast aside legacy. And that meant breaking up with Carlo. If she went any further down the proverbial rabbit hole with him and this relationship, she knew it would compromise her total devotion to food. To making Gaetano’s one of the best Italian restaurants in L.A. and beyond. Thereby forcing people to remember that Italian history—therefore, Italian food history—was still very much alive and breathing in the città degli angeli italiani.